Contents

![]() Gallery

Gallery

![]() Press Coverage

Press Coverage

![]() EDP

2 December 1987

EDP

2 December 1987

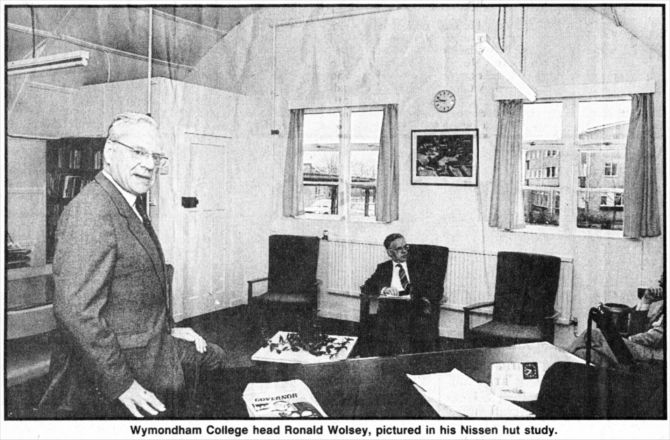

John Timpson on the phasing out of Wymondham College's famous Nissen huts

The instructions for finding the headmaster's study were an indication of what to expect. "Look for the bright green Nissen hut; the headmaster is inside it."

Driving into this school is like putting the clock back 40 years. Not 400 years, like some boarding schools, into a world of ivy-clad elegance with mellowed brickwork and mullioned windows set around ancient flagged courtyards. No, just 40 years, into the wartime bleakness of corrugated iron huts and crumbling brick outhouses, set around a grassed-over pit which some say was a dump for old Army lorries.

The Americans used these huts as an emergency hospital to cope with the casualties from the thousand-bomber raids they launched from their East Anglian bases. They came by the trainload to Wymondham station and were brought here to Morley by ambulance and bus and truck. The huts were built to take 750; they always held more.

Now they house not patients but pupils; they are the home of a school unique in the country, described when it was founded as one of the boldest and best educational experiments since the war, a co-educational state boarding school with the parents paying the boarding costs and the local authority paying for the tuition.

It was my first visit to Wymondham College. I discovered after a four-mile drive from Wymondham down the Al11, as hair-raising as ever, that it could have been called Attleborough College, since it is midway between the two - or even, as was once mooted but mercifully rejected, Morley Comprehensive.

We unearthed the original plan of the hospital and it is still easy to recognise the layout. The general wards are now classrooms: psychiatric cases were treated in what are now the science labs. The huts are heated from the same old boiler-house, still connected by pipes above ground so even the modern furnaces find it a tough battle against the Norfolk winter. The officers' accommodation was in the huts in one corner of the site, the nurses' in another, though no doubt there was a beaten path between the two. Each had one hut described on the map in abbreviated Army jargon, "Bath and Sanity", an unintentional tribute to the soothing powers of a good soak.

The brick mortuary still stands, but now it is a starting point instead of the finish. Part of it is used as a career guidance centre for school leavers. The original chapel has gone, but a new one has been created in a Nissen hut, with murals drawn by the pupils showing the site's history from the Iron Age to the Computer Age. The Saxons and Romans were there, so in due course was the Mid-Norfolk Golf Club.

When the Americans left after the war the hospital became a teachers' training centre. Then in 1951 it became Wymondham College, or as the prospectus described it, "a Technical School, Special Grammar School and Commercial Course, all of them residential." It had 90 pupils. Today it has 650 boarders and 250 sixth-form day pupils. It is the largest school of its kind in Europe, with an outstanding educational record. Even its sporting achievements are remarkable; the boys play both rugby football and soccer, and the school has just produced a Cambridge Blue for both. Yet all this is still centred on Nissen huts which were considered temporary, 40 years ago.

A Nissen hut can have its advantages. It is more spacious than it looks, and it can be extended or sub-divided in a matter of days, without too much paperwork being involved. In the early days it was done by the pupils themselves. The engineering department, for instance, was too small, so the headmaster and three of the staff led a working party of pupils to extend it. It prompted Sir Lincoln Ralphs, the former chief education officer who was the inspiration behind the college, to observe in 1953: "Nowhere in Norfolk is it more abundantly obvious that buildings do not make the school. Here, literally, the school has made the buildings."

But there were limits. Modern boarding houses were eventually built so the children no longer slept, as the American patients once did, in long rows inside the huts, un-insulated against the cold or indeed against the rats. Some years ago one boy unwise enough to leave a packet of sweets in his jacket pocket, hanging by his bed, awoke to find the sweets gone, along with most of the pocket ...

Masters who had a couple of the old side-wards or nurses' offices as bedroom and sitting-room were moved into flats in the new houses. Living conditions improved; teaching conditions did not. Norfolk County Council, footing the enormous maintenance and heating bills for the old huts and with the prospect of a much bigger bill to replace them, began to talk of closure. The parents united in the College's defence. There emerged a rescue plan which, like the College, is unique. The amount needed for new buildings so the huts could be demolished was £720,000. The parents undertook to raise half; the County Council agreed to match them, pound for pound. It was an arrangement unprecedented, I am told, in the history of major school appeals.

This week a new central dining hall is to be officially opened to release space in the boarding houses. There is enough money now for a new science block. The days of the Nissen huts are numbered; if the appeal target is reached, by 1989 only the sanatorium and the chapel will remain.

But as I walked around the school with some of the older pupils, the wind whipping through the inadequately-covered walkways between those rusting semi-circular relics, I got the impression that they took rather a pride in their bizarre scholastic surroundings. If there are happy associations, one can develop an affection even for a curved piece of corrugated iron. So Mr Nissen, wherever you are now, take heart when you see your creations finally disappear. Even when Wymondham College is housed entirely in bricks and mortar, I suspect four decades of pupils will still cherish your memory.